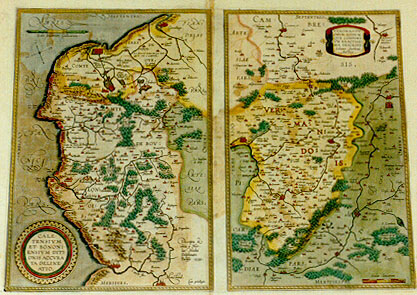

An annotated list of names is also provided together with the biographical details of cartographers, publishers, engravers etc. Among other things, provided are the postal and e-mail addresses of libraries, archives, auction houses, stores all over the world where a researcher can, either directly or via the Internet, familiarize oneself with electronic copies of these maps – the humankind’s historical heritage. The maps are presented in chronological order, including the image of a map together with its basic characteristics, bibliography, and storage locations, which makes it possible to use either directly the original or a quality copy of this particular map for further research. The book contains maps created by the world civilization up until 1700. This book has been created with the aim of discovering the cartographical monuments that have represented the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov from the earliest times. This paper's analysis of the aesthetic and political connotations of a map of the world speaks towards the versatility of an East Asian cartographic tradition which adapted Western cartographic elements to the concerns of the local audience. This dimension is reinforced by contemporary novels which co- opted ships into the spatial rhetoric of commercial success: for example, in Ihara Saikaku's novel ‘Japan's Treasury of the Ages’, published in the same year as Ryusen's map, the ambitious spirit of a merchant was compared to an ocean-going trade ship sailing to lands of treasure overseas.

This points to a performative aspect of this map – it was meant as a facilitator for travel aboard an imaginary drifting ship. Ryusen thus associated his identity as a cartographer to one of the iconographic elements of the map. We can get a hint of how the cartographer Ryusen envisioned the use of his maps by considering his choice of a seal with a variant of his name meaning 'drifting ship'. Secondly, I argue for a simultaneous dimension of this map: it enabled imaginary travel across the sea, at a time when this was not physically possible. The iconography of the Japanese ship in Ryusen's world map can thus be interpreted as symptom of a fear of invasion by the Qing Empire proliferating among the urban population which constituted the audience for such a map. Underlying this measure was a concern over an invasion of Japan by the Qing empire, expressed in the intellectual discourse of the period. This had an immediate impact on trade activity in Japan's only international port, Nagasaki: quotas were introduced for ships trading from China. Five years before the publication of this map, Qing forces had taken over the last outpost of the Ming loyalists, the maritime trade center of Taiwan. Firstly, I interpret this martial stance as projecting the image of a Japan ready for sea-battle against the forces of the Great Qing empire. However, I argue that this map projects an updated worldview specific to seventeenth century Japan, by including the depiction of a ship belonging to the Great Qing empire sailing towards a Japanese ship equipped for war. This map of the world has been interpreted as a mere pastiche of Western cartographic elements filtered through Matteo Ricci's production in China. I focus on Ishikawa Ryusen's 1688 reprint of ‘The General Map of All Countries’ (Bankoku sokai zu). This paper discusses the dual agency, both political and aesthetic, of seventeenth century cartographic production in Japan.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)